System Calls

Introduction

A system call is a controlled entry point into the kernel, allowing a process to request the kernel to perform some action on the process’s behalf. The kernel makes a range of services accessible to programs via the system call application programming interface (API). Application developers often do not have direct access to the system calls, but can access them through this API. These services include, for example, creating a new process, performing I/O, and creating a pipe for interprocess communication. The set of system calls is fixed. Each system call is identified by a unique number. The list of different system calls can be found here.

A system call changes the processor state from user mode to kernel mode, so that the CPU can access protected kernel memory. Each system call may have a set of arguments that specify information to be transferred from user space (i.e., the process’s virtual address space) to kernel space and vice versa. From a programming point of view, invoking a system call looks much like calling a C function.

Types of system calls

There are mainly 5 types of different system calls. They are :

- Process Control: These system calls are used to handle tasks related to a process such as process creation, termination,etc.

- File Management: These system calls are used for operations on files such as reading/writing a file.

- Device Management: These system calls are used to deal with devices such as reading/writing into device buffers.

- Information Maintenance: These system calls handle information and its transfer between the operating system and the user program.

- Communication: These system calls are useful for inter-process communication. They are also used for creating and deleting a communication connection.

| Types Of System Calls | Examples in Linux |

|---|---|

| Process Control | fork(),exit(),wait() |

| File Management | open(), read(),write() |

| Device Management | ioctl(),read(),write() |

| Information Maintenance | getpid(),alarm(),sleep() |

| Communication | pipe(),shmget(),mmap() |

User mode, kernel mode and their transitions

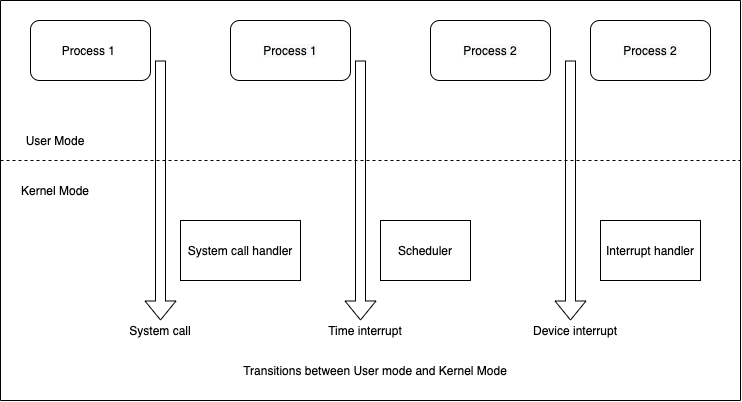

Modern processor architectures typically allow the CPU to operate in at least two different modes: user mode and kernel mode . Correspondingly, areas of virtual memory can be marked as being part of user space or kernel space. When running in user mode, the CPU can access only memory that is marked as being in user space; attempts to access memory in kernel space result in a hardware exception.

At any given time, a process may be executing in either user mode or kernel mode. The type of instructions that can be executed depends on the mode and this is enforced at the hardware level. CPU modes (also called processor modes, CPU states, CPU privilege levels) are operating modes for the central processing unit of some computer architectures that place restrictions on the type and scope of operations that can be performed by certain processes being run by the CPU. The kernel itself is not a process but a process manager. The kernel model assumes that processes that require a kernel service use specific programming constructs called system calls.

When a program is executed in user mode, it cannot directly access the kernel data structures or the kernel programs. When an application executes in kernel mode, however, these restrictions no longer apply. A program usually executes in user mode and switches to kernel mode only when requesting a service provided by the kernel. If an application needs access to hardware resources on the system(like peripherals,memory,disks), it must issue a system call, which causes a context switch from user mode to kernel mode. This procedure is followed when reading/writing from/to files, etc. It is only the system call itself which runs in kernel mode, not the application code. When the system call is complete, the process returns to the user mode with the return value using an inverse context switch. Apart from system calls, kernel routines can be activated in the below ways as well:

- The CPU executing the process signals an exception , which is an unusual condition such as an invalid instruction. The kernel handles the exception on behalf of the process that caused it.

- A peripheral device issues an interrupt signal to the CPU to notify it of an event such as a request for attention, a status change, or the completion of an I/O operation. Each interrupt signal is dealt by a kernel program called an interrupt handler . Since peripheral devices operate asynchronously with respect to the CPU, interrupts occur at unpredictable times.

- A kernel thread is executed. Since it runs in kernel Mode, the corresponding program must be considered part of the kernel.

In the above diagram, Process 1 in User Mode issues a system call, after which the process switches to Kernel Mode and the system call is serviced. Process 1 then resumes execution in User Mode until a timer interrupt occurs and the scheduler is activated in Kernel Mode. A process switch takes place and Process 2 starts its execution in User Mode until a hardware device raises an interrupt. As a consequence of the interrupt, Process 2 switches to Kernel Mode and services the interrupt.

Working of write() system call

The write() system call writes data to an open file.

# include <unistd.h>

ssize_t write(int fd, void *buffer, size_t count);

buffer is the address of the data to be written; count is the number of bytes to write from buffer; and fd is a file descriptor referring to the file to which data is to be written.

write() call writes up to count bytes from buffer to the open file referred to by fd. On success, write() call returns the number of bytes actually written, which may be less than count and returns -1 on error. When performing I/O on a disk file, a successful return from write() doesn’t guarantee that the data has been transferred to disk, because the kernel performs buffering of disk I/O in order to reduce disk activity and expedite write() calls. It simply copies data between a user-space buffer and a buffer in the kernel buffer cache. At some later point, the kernel writes (flushes) its buffer to the disk.

If, in the interim, another process attempts to read these bytes of the file, then the kernel automatically supplies the data from the buffer cache, rather than from (the outdated contents of) the file. The aim of this design is to allow write() to be fast, since they don’t need to wait on a (slow) disk operation. This design is also efficient, since it reduces the number of disk transfers that the kernel must perform.

Debugging in Linux with strace

strace is a tool used to trace the transition between user processes and the Linux kernel. Inorder to use the tool, we need ensure that it is installed in the system by running the command:

$ rpm -qa | grep -i strace

strace-4.12-9.el7.x86_64

If the above command does not give any output, you can install the tool via:

$ yum install strace

The functions which are a part of standard C library are known as library functions. The purposes of these functions are very diverse, including such tasks as opening a file, converting a time to a human-readable format, and comparing two character strings. Some library functions are layered on top of system calls. Often, library functions are designed to provide a more caller-friendly interface than the underlying system call. For example, the printf() function provides output formatting and data buffering, whereas the write() system call just outputs a block of bytes.The most commonly used implementation of the standard C library on Linux is the GNU C library glibc.

The C programming language gives printf() that lets the user write data in many different formats. So printf() as a function converts your data into a formatted sequence of bytes and that calls write() to write those bytes onto the output. Let us examine what happens when a printf() statement is executed with the use of strace command : strace printf %s “Hello world”

~]$ strace printf %s "Hello world"

execve("/usr/bin/printf", ["printf", "%s", "Hello world"], [/* 47 vars */]) = 0

brk(NULL) = 0x90d000

mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f8fc672f000

access("/etc/ld.so.preload", R_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

open("/etc/ld.so.cache", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

fstat(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=98854, ...}) = 0

mmap(NULL, 98854, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, 3, 0) = 0x7f8fc6716000

close(3) = 0

open("/lib64/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

read(3, "\177ELF\2\1\1\3\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\3\0>\0\1\0\0\0\20&\2\0\0\0\0\0"..., 832) = 832

fstat(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0755, st_size=2156160, ...}) = 0

mmap(NULL, 3985888, PROT_READ|PROT_EXEC, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0) = 0x7f8fc6141000

mprotect(0x7f8fc6304000, 2097152, PROT_NONE) = 0

mmap(0x7f8fc6504000, 24576, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0x1c3000) = 0x7f8fc6504000

mmap(0x7f8fc650a000, 16864, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f8fc650a000

close(3) = 0

mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f8fc6715000

mmap(NULL, 8192, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f8fc6713000

arch_prctl(ARCH_SET_FS, 0x7f8fc6713740) = 0

mprotect(0x7f8fc6504000, 16384, PROT_READ) = 0

mprotect(0x60a000, 4096, PROT_READ) = 0

mprotect(0x7f8fc6730000, 4096, PROT_READ) = 0

munmap(0x7f8fc6716000, 98854) = 0

brk(NULL) = 0x90d000

brk(0x92e000) = 0x92e000

brk(NULL) = 0x92e000

open("/usr/lib/locale/locale-archive", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

fstat(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=106075056, ...}) = 0

mmap(NULL, 106075056, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, 3, 0) = 0x7f8fbfc17000

close(3) = 0

open("/usr/share/locale/locale.alias", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

fstat(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=2502, ...}) = 0

mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f8fc672e000

read(3, "# Locale name alias data base.\n#"..., 4096) = 2502

read(3, "", 4096) = 0

close(3) = 0

munmap(0x7f8fc672e000, 4096) = 0

open("/usr/lib/locale/UTF-8/LC_CTYPE", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

fstat(1, {st_mode=S_IFCHR|0620, st_rdev=makedev(136, 1), ...}) = 0

mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x7f8fc672e000

write(1, "Hello world", 11Hello world) = 11

close(1) = 0

munmap(0x7f8fc672e000, 4096) = 0

close(2) = 0

exit_group(0) = ?

+++ exited with 0 +++

execve("/usr/bin/printf", ["printf", "%s", "Hello world"], [/ 47 vars /]) = 0

The first system call made is execve() and does three things:

- The operating system (OS) stops the duplicated process (of the parent).

- OS loads up the new program (in this case: printf()), and starts the new program.

- execve() replaces defining parts of the current process's memory stack with the new stuff loaded from the printf executable file.

The first word of the line, execve, is the name of the system call being executed. The first parameter must be the path of a binary executable or a script. The second is an array of argument strings passed to the new program. By convention, the first of these strings should contain the filename associated with the file being executed. The third parameter must be an environment variable. The number after the = sign (which is 0 in this case) is a value returned by the execve system call which indicates that the call was successful.

open("/usr/lib/locale/UTF-8/LC_CTYPE", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

In this line, the program tried to open() file /usr/lib/locale/UTF-8/LC_CTYPE. However the system call failed (with -1 status) with the descriptive error message No such file or directory, as the file wasn’t found (ENOENT).

brk(NULL) = 0x90d000

brk(0x92e000) = 0x92e000

brk(NULL) = 0x92e000

The system call brk() is used to increase or decrease the process’s data segment. It returns the new address where the data segment of the process is to end.

open("/lib64/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

read(3, "\177ELF\2\1\1\3\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\0\3\0>\0\1\0\0\0\20&\2\0\0\0\0\0"..., 832) = 832

In the above lines of the console output, we see that a successful open() call is made, followed by read() system call.

In open(), the first parameter is the path to file which you want to use and the second parameter defines the permissions. In this example, O_RDONLY which means the file is read only and O_CLOEXEC which enables the close-on-exec flag for the opened file. This is useful to avoid race conditions in multithreaded programs where one thread opens a file descriptor at the same time as another thread. 3 indicates the file descriptor used to open the file. Since fd 0, 1, 2 are already taken by stdin, stdout and stderr. So first unused file descriptor is 3 in file descriptor table.

If open()

In read(), the first parameter is the file descriptor which is 3(the file was opened using this file descriptor by open(). The second parameter is the buffer to read data from and the third parameter is the length of the buffer. The return value is 832 which is the number of bytes read.

close(3) = 0

A close system call is used to close a file descriptor by the kernel. For most file systems, a program terminates access to a file in a filesystem using the close system call. 0 after the = sign indicates that the system call was successful.

write(1, "Hello world", 11Hello world) = 11

In the previous section, we described the write() system call and the arguments that it takes. Whenever we see any output to the video screen, it’s from the file named /dev/tty and written to stdout on screen through fd 1. The first parameter is the file descriptor , second parameter is the buffer containing the information to be written and the last parameter contains the count of characters. On success, the number of bytes written are returned (zero indicates nothing was written) which is 11 in this example.

+++ exited with 0 +++

This indicates that the program exited successfully with exit code 0. An exit code of 0 generally indicates successful execution and termination in Linux programs.

You don't need to memorize all the system calls or what they do, because you can refer to documentation when you need to. Ensure the following package is installed before running the man command:

$ rpm -qa | grep -i man-pages

man-pages-3.53-5.el7.noarch

Run the following man command with the system call name to see the documentation for that system call(for eg, execve):

man 2 execve

Apart from system calls, strace can be used to detect the files that are being accessed by the program. In the above trace, we have a system call open("/lib64/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3 which is opening the libc shared object /lib64/libc.so.6 which is the C implementation of various standard functions. It is the file where we see the printf() definition needed for printing Hello World.

Strace can also be used to check if a program is hanging or stuck. When we have the trace, we can observe at which operation the program is stuck as well. Furthermore, as we go through the trace, we can also find errors(if there are any) to point out why the program is hung/stuck. Strace can be very helpful in finding the reason behind slow performance of a program.

Alhough strace has the aforementioned uses to it, if you're running a trace in a production environment, strace is not a good choice. It introduces a substantial amount of overhead. According to a performance test conducted by Arnaldo Carvalho de Melo, a senior software engineer at Red Hat, the process traced using strace ran 173 times slower, which can be disastrous for a production environment.